Caves in the Aggtelek and Slovak Karst (World Heritage)

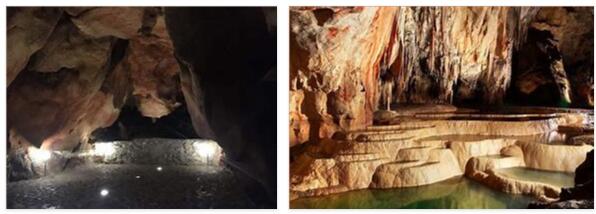

The World Heritage Site in the south of the Slovak Republic on the border with Hungary includes the largest karst area in Central Europe. Visit clothesbliss.com for Hungary travel destinations. There are more than 1000 caves here as well as numerous gorges and underground streams. The bizarre stalactite formations in the caves are impressive evidence of the special landscape of the Karst.

Caves in the Aggtelek and Slovak Karst: facts

| Official title: | Caves in the Aggtelek and Slovak Karst |

| Natural monument: | Karst landscape developed for tourism since 1930, the Hungarian Aggtelek Karst (197.08 km²) placed under landscape protection since 1978, national park since 1985, Slovak Karst (361.65 km²) placed under landscape protection since 1973; The World Heritage area is, as it only includes the 712 caves that have been discovered and explored so far, much smaller: the Baradla Domica cave system with a length of 21 km, with a natural hall for 1000 visitors, the world’s largest stalagmite with a height of 32.7 m, formations such as “Roman Baths” and “Maiden Walk” as well as the underground river Styx; Finds i.a. from the time of the Bükk culture (6400-6100 BC) |

| Continent: | Europe |

| Country: | Hungary / Slovak Republic |

| Location: | Border area between the southern Slovak Republic and northeastern Hungary, southwest of Kosice |

| Appointment: | 1995 |

| Meaning: | the most intensively studied European karst landscape of particular aesthetic charm |

| Flora and fauna: | Beetles such as Duvalius bokori bokori, insects such as Limonia nubeculosa, Tarnania fenestralis and Eccoptomera obscura, cave worms such as Peloscolex velutinus and Rhyacodrilus falciformis, molluscs such as spring snail and common pea mussel, and the species Nebula agonica, also the common snail agaristica, the sadgannonian creeper, which only occurs here fossarum |

A journey in space and time

The nature reserve Aggtelek Caves and the foothills of the Slovak Ore Mountains are among the characteristic examples of European karst formations, and the more than 700 caves discovered here are among the most scientifically explored on the continent. Exploring this underworld on a guided tour is not a particularly physically demanding undertaking. On a tour you reach the river Styx, along whose muddy river bed you can wade along with a little effort and after about a kilometer you can reach the Slovak part of the cave system, the Domica cave: nature knows no national borders.

For a short moment it is absolutely silent, until suddenly thunderous applause replaces the last sounds of the »Sinfonietta Hungaria« concert. The audience was enchanted by the unique acoustics and the peculiar atmosphere in the midst of bizarre stalactite formations. A cold shower runs down the spine of one or the other, because despite warming jackets it has become very cool: Down here in the imposing concert hall of the Baradla Cave, even in the middle of summer, the average temperature of the moisture-enriched air is only ten degrees Celsius. But that hasn’t stopped anyone from enjoying a concert in the longest cave in the temperate zone, adorned with fantastic stalactites.

Even in the Tertiary, a large, shallow sea billowed over the 550 square kilometer karst area on both sides of the Hungarian-Slovakian border. Over time, thick layers of limestone were deposited in the shallower water; a prerequisite for the geomorphological process that is so characteristic of this region. Weathering shaped the landscape, causing the limestone layers to collapse here and there, leaving behind funnel-shaped so-called “sinkholes”. But there were also plateaus in which watercourses suddenly disappear from the surface to flow through underground caves and finally come back to daylight at the foot of the mountains in the form of abundant “karst springs” – sometimes petrified.

The rugged appearance of a limestone landscape is due to the chemical weathering of calcite, the main component of the rock, which dissolves in the weak acidity of the rainwater. On the surface, this takes place most quickly along faults. Over time, the cracks get wider and wider, and so-called carts are formed, rock ribs separated from one another by gullies. These rainwater drainage channels are popularly called “devil’s furrows”.

Karstification began two million years ago: water played an important role not only in the design of the cavities, but also in their decoration. Calcareous precipitation seeped through the limestone cover layer and formed pencil-thick, macaroni-like tubes on the cave ceiling, which over time developed millimeter by millimeter into huge ceiling cones – called stalactites. The drops falling from the lower end of the stalactites onto the cave floor led to the formation of soil cones – so-called stalagmites. Over time, these natural structures can reach heights of several dozen meters with steady growth. In the Krásnohorska Cave of the cave system, the highest stalagmite in the world can be found, which reaches a height of almost 33 meters and is called the »observatory«.

In the underworld, aragonite rosettes, rich sinter decorations and ice-filled abysses, especially when you consider the location above sea level, are a unique phenomenon in Central Europe. Archaeological finds, such as pots, stone tools, bones and fireplaces, suggest that the gigantic underground wonderland was inhabited since the Neolithic and served as a cult and burial site: a unique museum of geological history.